Willendorf to Baartman: Venus, BBLs and the African Body

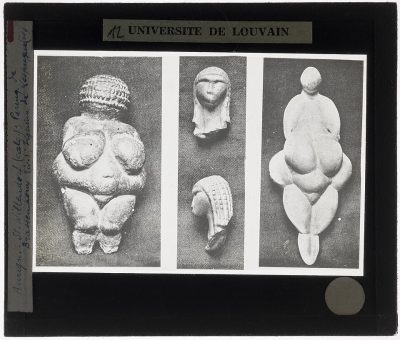

Venus of Willendorf is an 11.1-centimetre-tall (4.4 in) Venus figurine estimated to have been made c. 30,000 years ago, and found in Austria in 1908 (Image: Wiki Commons)

The Ancient Venuses of Europe

Why has the African female body been such a site of fascination, projection, and sometimes exploitation? From the limestone Venus of Willendorf, carved nearly 30,000 years ago in Ice Age Europe, to the tragic spectacle of Sarah Baartman, paraded through 19th-century Europe as the so-called Hottentot Venus, the story is tangled, uncomfortable, and deeply revealing.

In the early 20th century, archaeologists found dozens of small Paleolithic figurines, popularly called “Venus statues,” scattered across Europe and Eurasia. The most famous, the Venus of Willendorf, shows a woman with rounded hips, prominent buttocks, and exaggerated curves. Others, like the Venus of Brassempouy, even appear to show braided hair or woven caps, suggesting complex cultural aesthetics. Scholars believe that artists in Ice Age Europe carved these small statues with exaggerated hips, large breasts, and rounded bottoms as symbols of fertility and life. Interestingly, some of these statues have carvings on their heads that look like braids or cornrows. This has led some scholars to believe that these figurines might show an early link to African women, suggesting that this curvy body type was a symbol of beauty and life from the very beginning.

Were these fertility charms? Self-portraits of women? Or artistic celebrations of abundance in a harsh Ice Age world? The truth is still debated. But one fact is clear: these figures echo bodily features often associated with African physiologies, especially among the Khoisan people of Southern Africa.

Enter Sarah Baartman

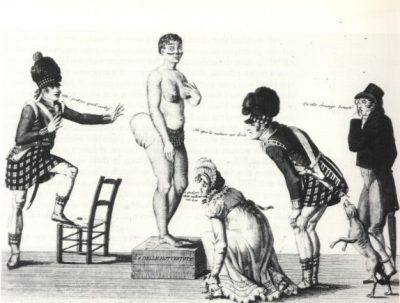

Track back to the early 19th century,1810 to be precise, when a young Khoikhoi woman named Sarah (Saartjie) Baartman was taken from the Cape Colony to Europe. There, she became a spectacle: put on stage in London and Paris, displayed for her steatopygia, the same prominent buttocks that prehistoric sculptors had carved thousands of years before. Europeans gave her a cruel nickname: the Hottentot Venus. By linking her body to the ancient figurines, they cast Baartman as a living fossil, proof (they thought) of Africa’s “primitive” connection to humanity’s past. It was less admiration and more dehumanization; a way of placing Africans outside of modernity.

Was this projection or continuity? Here lies the tension: were Europeans simply projecting their fantasies onto both the figurines and Baartman? Or do these echoes suggest a deeper truth: that ideals of fertility, survival, and beauty have African roots carried into Europe by humanity’s earliest migrants?

Afrocentric scholars argue that the Venus figurines may preserve a faint memory of the African mother archetype; a symbol of life, continuity, and abundance. In this view, Sarah Baartman’s physiology was not freakish, but a living echo of humanity’s oldest ideals of womanhood. Afterall, the woman’s features were a natural feature for some in her community. Europeans paid to see her as if she were a curiosity, linking her body to the ancient Venus statues but stripping away any sense of respect. Casting her body shape as “primitive” was a way of proving her captive’s superiority. Her story is a painful example of how the same body type once celebrated could be used to dehumanize and objectify a woman.

19th century French print “La Belle Hottentot” (The beautiful Hottentot) of Saartjie Baartman (Image: Wiki Commons)

The BBL: A New Ideal or a Lingering Past?

Today, the very body shape that was used to humiliate Sarah Baartman is now a global beauty ideal. Thanks to social media and celebrities, the BBL has become one of the most popular cosmetic surgeries in the world. People of all races now seek to achieve the same curves that were once mocked and gawked at. This modern trend brings up some big questions. Is it a new form of empowerment, where women are taking control of their bodies? Or is it simply a new kind of objectification, where a body type that was once shamed is now commodified and sold?

The obsession with the Brazilian Butt Lift (BBL) is more than a trend; it’s the latest chapter in a long, complicated story about how we see the female body, especially the Black female body. It’s a story that stretches from ancient stone figurines to a woman who was put on display, and it shows how a body type once ridiculed is now a global beauty standard.

The story of Venus forces us to ask: Why do certain body types become symbols of fertility or spectacle? Who gets to define beauty, and who gets reduced to an object? And how much of what we think is “European prehistory” is, in fact, a reflection of Africa’s enduring presence at the root of humanity? Perhaps we should not tie a neat bow on this history. What we can do is interrogate the links: between Willendorf and Baartman, between ancient symbols and modern exploitation, between admiration and objectification. Somewhere in this messy overlap lies a bigger story about memory, migration, and the politics of the female body that still shapes conversations about race, gender, and history today. Do the Venus figurines echo of an African archetype of womanhood, or simply European projections? And what lessons does Sarah Baartman’s story hold for how we see women’s bodies today?

The journey from the Venus figurines to Sarah Baartman and now to the BBL shows us that the way we view the female body is a powerful, and at times unsettling, part of history.

#BeautyStandards #FeministHistory #CulturalAppropriation #BodyPositivity #BBL #BodyImage #History #SarahBaartman

Recommended:

Unethical Experiments on Black People

White-Washed: The Missing Black Populations of North Africa

Vanishing Echoes: Black Populations Are Disappearing

African DNA: Humanity’s Deepest Roots & Cradle of Diversity