Africa of my Youth: Travel, Trade & Tradition in the Past

"The sap would... provide additional nutrition to the mother's milk. Those trees are all gone now."

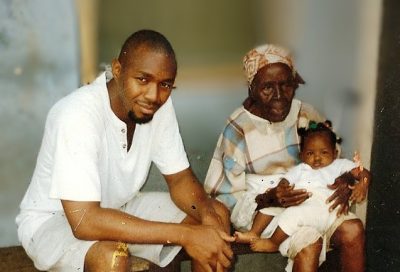

Multi-generational households are nurturing for the entire family.

Travel, Trust, and Tradition: The Africa of My Youth

In the Africa of my youth, travel meant walking. We walked everywhere. Cars were rare, and public transport only operated on set days. But we didn’t mind. Walking was part of life—sometimes a necessity, sometimes a joy.

Every two weeks, my family would walk to the next village, a 29-kilometre round trip. We helped our parents trade fresh farm produce at the village market. On the way, we’d pass farmland and stop to rest. Often, the men would stage impromptu wrestling matches—just for fun, after all that walking!

Nature Was Our Pharmacy

One day, my father had a terrible cough. Instead of heading to a clinic, we walked into the nearby forest. He searched carefully until he found a particular tree. With his machete, he bruised the bark, leaned in, and drank the sap that trickled out. Within hours, his cough disappeared.

Another tree was cherished for newborns. Elders would cut into its trunk at sunset and place a calabash beneath to collect its sap. By dawn, the calabash would hold nearly four litres. This nourishing liquid helped cleanse babies’ systems and boost mothers’ breast milk.

Sadly, those trees are gone now, lost to time, deforestation, and modern development. But their memory lingers.

Our Elders Were Never Alone

We had deep respect for the elderly. When a young man started his family, he built his house close to his parents, usually on family land. It kept generations close.

As parents aged, their children and grandchildren cared for them. If an elder had no children, nephews or nieces stepped in. We did not abandon our old ones. Even today, though many bring their parents to live in cities, the core tradition continues.

Our elders never lived—or died—alone.

Trading Was Built on Trust

On days between market trips, farmers placed goods along the roadside for sale. No one stood guard. Instead, twigs and leaves indicated the asking price. If you wanted to buy, you left cowries (the currency at the time), under the leaves and took the goods.

Didn’t agree with the price? Rearrange the twigs to suggest your offer, and walk away. On your return, if the seller accepted, the changed arrangement told you to leave your price and take the item. No words. No bargaining. No surveillance. Just mutual respect.

Stealing was almost unheard of. If a hungry student passed by and had no money, they could eat the fruit and leave the skin behind. It signaled that the food was taken out of need, not greed. No one took more than they needed, and everyone understood.

A Life We Should Not Forget

The Africa of my youth was simple, sustainable, and full of dignity. We lived in harmony with the land. We cared for our elders. We traded without cheating. And we healed ourselves with nature.

So much has changed. Fast roads have replaced long walks. Plastic replaces calabashes. Price tags now come with scanners. But what we had was special. It was rooted in community, built on trust, and rich with ancestral wisdom.

As we modernize, let’s not forget the values that made our way of life strong. Let’s remember the Africa of our youth—not just as a memory, but as a model worth preserving.

– Contributions by Eyelua R. M. Oshin (deceased) and Mrs Tomileye Adedipe (deceased)

If you wish to contribute a similar story to this article, please send an email to: externalaffairs@feelnubia.org.uk