Stolen Treasures of Tutankhamun Return to Egypt

Stolen Treasures of Tutankhamun Return to Egypt After 80 Years

After nearly a century in foreign hands, a precious collection of artefacts stolen from the tomb of Egypt’s legendary boy-king, Tutankhamun, is finally returning home. On November 10, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York returned 19 items to Egypt—small in size, but monumental in cultural value.

This return, though long overdue, marks a historic gesture in the global movement for the restitution of African heritage.

A Long-Awaited Homecoming

The artefacts—many of which fit in the palm of a hand—include two gold rings bearing the boy-king’s name, a miniature black-bronze dog with a gold collar, and a stunning broad necklace made of purple-blue beads. At 32 cm by 12 cm, the necklace is the largest of the returned items.

For Zahi Hawass, Egypt’s former antiquities chief, this moment was powerful.

“It’s a wonderful gesture,” he said, visibly moved.

The Metropolitan Museum’s director, Thomas Campbell, admitted what had long been known but never formally acknowledged:

“These objects were never meant to have left Egypt… The evidence shows without a doubt that they originated from Tutankhamun’s tomb.”

It was a quiet but powerful concession. One that echoes the demands of millions of Africans and heritage activists: our ancestors’ treasures belong at home.

Discovered, Plundered, and Displayed

When British archaeologist Howard Carter discovered Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings, the world was stunned. The tomb’s entrance was sealed with an unbroken royal stamp, appearing untouched. But Egyptologists later discovered that the tomb had been robbed shortly after its sealing around 1324 B.C., possibly through a hole in one of its outer walls.

At the time, Egyptian law allowed foreign excavators to keep many of the artefacts they uncovered. This legal loophole, combined with colonial power dynamics, meant that priceless treasures were quietly whisked away to museums in Europe and America.

Between 1922 and 1940, artefacts from the tomb entered the collections of Western institutions—sometimes through official channels, often through dubious ones. What was clear from the beginning was that these items were not souvenirs—they were sacred relics of an ancient African civilization.

Egypt Pushes Back

It wasn’t long before the Egyptian government began pushing back.

After a decade of large-scale excavations, Egypt realized the full value—cultural, spiritual, and financial—of the ancient tombs. The Valley of the Kings, home to generations of pharaohs from the 16th to 11th centuries B.C., became a protected site. In 1979, it was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site, cementing its global importance.

Egypt began to tighten controls and advocate for the return of artefacts taken during colonial rule. The recent return of the 19 Tutankhamun artefacts is a significant win in this decades-long campaign.

Who Was Tutankhamun?

Born in 1341 B.C., Tutankhamun was the son of the heretic Pharaoh Akhenaten and one of his sisters. Originally named Tutankhaten, meaning “Living Image of Aten,” he later changed his name to Tutankhamun—“Living Image of Amun”—to reflect the religious restoration that occurred during his reign.

He became pharaoh at just nine years old, ruling from 1333 to 1324 B.C. Though his reign was brief and largely unremarkable in terms of military conquests or political achievements, Tutankhamun became one of the most famous figures in ancient history.

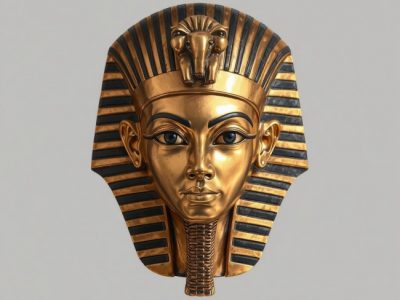

Why? Because his tomb was one of the best-preserved ever found—and its contents, including the iconic golden death mask, have toured the world, dazzling millions.

A King, A God, A Global Icon

Tutankhamun was deified in his own lifetime—one of the few pharaohs to be worshipped as a living god. A stela found at Karnak, dedicated to Amun-Re and Tutankhamun, suggests that people prayed to him directly for healing and forgiveness.

His cult reached far and wide. Temples in Kawa and Faras in Nubia (modern-day Sudan) were dedicated to him. Titles of officials even included references to the worship of Tutankhamun—evidence of his widespread spiritual significance across Africa.

In 2010, scientists used DNA testing and CT scans on his mummy. They concluded that the boy-king died at around age 19, likely from a combination of malaria and an infected leg fracture. Though young and frail in life, his legacy has endured for over 3,000 years.

The Looted Legacy

Tutankhamun’s treasures have travelled more than most people in the modern world. His artefacts have been displayed in Japan, France, Canada, West Germany, the USSR, and the USA, attracting millions of visitors.

The U.S. exhibition, organized by the Metropolitan Museum, ran from 1976 to 1979 and was seen by over eight million people. The gold death mask, the miniature animals, the ornate jewellery—they became symbols of ancient Egyptian grandeur and African ingenuity.

But behind this spectacle was a darker truth: many of these treasures had been stolen, smuggled, or acquired under dubious agreements. Some were sold on the black market. Others were gifted in exchange for political favours or kept by archaeologists as trophies of colonial conquest.

Restitution Is Justice

The Met’s recent return is just one step in a broader journey. The museum still holds over 36,000 Egyptian artefacts, spanning from the Paleolithic to the Roman periods.

The Egyptian government continues to call for the return of key cultural items, including the Rosetta Stone, currently housed in the British Museum. Across Africa, countries like Nigeria, Ethiopia, and Benin are making similar demands for the return of looted heritage.

The momentum is building. As more museums acknowledge the unethical ways in which these artefacts were obtained, the case for restitution grows stronger.

The Grand Egyptian Museum: A New Home for Old Glory

Once returned, the Tutankhamun artefacts will join over 5,000 items in the Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM) in Giza, which is set to be the largest archaeological museum in the world. It will sit close to the Great Pyramids, restoring ancient treasures to their rightful setting—on African soil, under African skies.

The new museum aims to not only display Egypt’s ancient glory but also tell the story of its struggle to reclaim its history. It will be a space where young Egyptians, Africans, and global visitors can connect with a civilization that shaped the world.

Why It Matters

The return of Tutankhamun’s artefacts is about more than just museums and collections. It’s about dignity, identity, and justice.

These treasures tell the story of an African king who was worshipped as a god, whose short life left an eternal legacy. They remind us that African civilizations were sophisticated, artistic, and spiritually rich long before colonialism distorted the narrative.

Feelnubia celebrates this victory not just for Egypt, but for the whole of Africa. The homecoming of Tutankhamun’s treasures is a step toward correcting historical wrongs—and restoring pride in our shared heritage.

The boy-king is finally coming home. And with him comes the truth.

The British Metropolitan Museum has about 36,000 Egyptian objects dating from the Paleolithic to the Roman period

Similar stories @ “Africa is Greece”