Africa’s Forgotten Scripts: 10 Indigenous Writing Systems

Meriotic script (Image: Wiki Commons)

Africa Wrote First

Africa is the cradle of humanity, and it is also one of the world’s earliest cradles of writing. Long before colonial ink touched African soil, communities from the Nile Valley to the Congo were crafting systems to record law, lineage, spirituality, and science. Yet, these systems were buried under colonial narratives that cast Africa as “preliterate.”

Understanding the shared DNA among Africa’s diverse writing systems helps reveal how Africans thought about memory, power, and knowledge. While each script has its own story, they share notable similarities across three main dimensions: form, function (use), and modern prominence. Despite being spread across different regions and cultures, many African writing systems share features. Often choosing symbolism over phonetics, systems like Nsibidi, Lukasa, and early Bamum emphasized visual symbols or mnemonic cues instead of writing down sounds or words directly.

These scripts functioned more like conceptual maps than phonetic alphabets. These forms prioritize meaning and memory over literal spelling, a distinctly African way of encoding knowledge. Several scripts blend pictographs with ideographs and syllables. For instance, Meroitic scripts and Geʽez use elements of both alphabetic and syllabic systems. Ajami and Tifinagh adapt foreign scripts (Arabic or Libyco-Berber) for local expression.

African writing systems were also used in tactile or multisensory Form. Lukasa is a tactile record system—touching beads prompts memory recall. Nsibidi was inscribed on skin (tattoos, scarification), clothing, walls, or ritual objects.

Let us take you on a journey through ten of the continent’s most brilliant and often forgotten indigenous systems of writing and record-keeping.

1. Egyptian Hieroglyphics (c. 3200 BCE – Egypt/Sudan)

Hieroglyphics are a logographic, ideographic, and phonetic script type that was used in temples, tombs, religious texts, and cosmic philosophy.

Hieroglyphics are among the oldest scripts in human history. More than symbols, each glyph carried spiritual weight. Pharaohs carved them on stone for immortality, and scribes inked them onto papyrus scrolls such as the Book of the Dead. These were not just stories; they were cosmic maps.

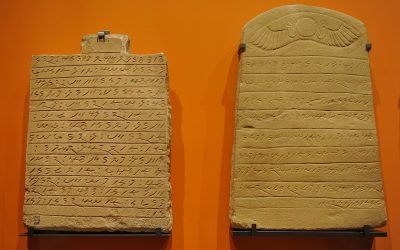

2. Meroitic Script (c. 300 BCE – Ancient Nubia, Sudan)

The Meriotic script was both alphabetic and syllabic. It was used to issue royal decrees, for religious rites, and for documenting monuments.

Developed by the Kushites of Nubia, this script marked a cultural departure from Egypt. Though not fully deciphered today, it was used in inscriptions on pyramids and temples, representing Africa’s first indigenous written language south of Egypt.

3. Nsibidi (Pre-16th Century – Nigeria/Cameroon)

Nsibidi was a symbolic/ideographic script used by secret societies for internal communication, love letters, and for maintaining a record of laws and rituals.

Predating colonial records, Nsibidi was a secret code of symbols used by the Ejagham, Igbo, and Efik peoples. It was also written on textiles, walls, and calabashes. Nsibidi communicated abstract ideas such as justice, strength, and desire. It was taught by initiated elders and women.

4. Lukasa Memory Boards (Luba Kingdom – DR Congo)

The Lukas memory boards were non-written mnemonic devices used to record oral history, genealogy, and rituals.

Rather than text, the Luba used tactile memory boards embedded with beads and shells. Trained oral historians, the Mbudye, used them to recite lineage, battles, and rituals. This was a record system for the fingers and the soul.

5. Tifinagh (Ancient to Modern Tuareg/Berber Nations)

Tifinagh was an alphabetic script that was used for body scarification (tattoos), poetry, signs, and cultural preservation

Tifinagh is a living script, still taught in Amazigh schools in Algeria and Mali. Used primarily by Tuareg women, it expresses identity and resistance in the face of cultural erasure. Its ancestor, the Libyco-Berber script, dates back over 2,500 years.

6. Geʽez Script (Ancient Aksum to Modern Ethiopia & Eritrea)

The Ge’ez script was a syllabary (abugida) writing system used for religious purposes, science, law, and literature.

Geʽez is the script of the ancient Aksumite Empire and the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. Today, it remains in use as a liturgical language, and its script is central to languages like Amharic and Tigrinya. It has preserved Christian African theology and science for over 2000 years.

7. Ajami (West Africa)

Ajami is a modified Arabic alphabet script that is still used today for writing African languages such as Hausa, Yoruba, and Wolof in Islamic contexts.

Ajami represents the fusion of Islamic scholarship with African vernaculars. Long before colonizers introduced the Latin alphabet, Ajami was the written medium for poetry, law, politics, and history. It was, and remains, a literary tradition of resistance.

8. Vai Script (Liberia, 1833 CE)

The Vai script was a syllabary script that was invented by Momolu Duwalu Bukele. It was used for letters, folktales, and contracts.

The Vai people of Liberia invented this writing system without foreign influence. It’s still taught in schools and was digitized into Unicode in recent years. Vai script proves Africa’s post-contact innovation and literacy didn’t die with colonization.

9. Bamum Script (Cameroon, ~1896 CE)

The Bamum script evolved from pictograms to a syllabary. Invented by King Ibrahim Njoya, it was used to keep palace records, laws, medicine, and religion.

The Bamum script evolved through six stages, a rare case of a language consciously refined over time. Today, the Bamum Palace holds an archive of manuscripts, maps, and scientific writings, which are a crown jewel of African literacy.

10. Hieratic & Demotic Scripts (Ancient Egypt)

The Hieratic and Menotic scripts are cursive forms of hieroglyphics that were used for legal documents, literature, and letters.

Priests and scribes used hieratic for sacred texts; Demotic was its secular cousin. They represent the evolution of African bureaucratic and literary sophistication, long before Rome had codified law.

Similarities in Use

Across time and space, these systems were used in remarkably parallel ways, which include spiritual and ritual purposes. Hieroglyphics, Nsibidi, and Lukasa were all deeply connected to religious or mystical institutions. Access was often restricted, known only to priests, scribes, elders, or secret societies (like Ekpe or Mbudye).

Key to keeping records of political legitimacy and governance, scripts like Geʽez, Bamum, Meroitic, and Hieratic/Demotic were used to issue royal decrees, preserve genealogies, and codify law. Writing reinforced authority and history. “If it is written, it is known.”

Tifinagh, Vai, and Ajami were used to teach language and culture, particularly in areas where colonial systems sought to erase them. Many of these scripts were used in schools, manuscripts, poetry, and trade, fostering communal knowledge transmission. Furthermore, writing in Africa was not just about record-keeping; it was about stewarding identity, lineage, and divine order.

| Feature | Examples | Shared Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| Symbolic Form | Nsibidi, Lukasa, Hieroglyphs | Visual-conceptual over phonetic |

| Restricted Use | Nsibidi, Hieratic, Lukasa | Reserved for initiated or elite |

| Spiritual Function | Hieroglyphs, Nsibidi, Geʽez | Sacred rituals, cosmology |

| Political Legitimacy | Meroitic, Bamum, Ajami | Used to issue royal or legal texts |

| Cultural Preservation | Tifinagh, Vai, Ajami | Taught in schools, revived digitally |

| Modern Revival | Vai, Bamum, Tifinagh | Unicode inclusion, museum archives |

Revival and Digitization

Many African scripts are undergoing a renaissance as tools of cultural healing, activism, and education. Scripts like Nsibidi and Lukasa are lesser known outside academic or artistic circles, yet they’re influencing Afrofuturist art, fashion, and design.

Keen to preserve these writing systems, others like Tifinagh, Vai, and Geʽez are being taught in schools and incorporated into Unicode fonts, keyboard apps, and digital platforms. The Bamum script has its digital archive and museum in Cameroon.

Ajami, Tifinagh, and Vai are celebrated today as symbols of cultural pride and postcolonial identity, demonstrating the resilience of African intellect, which has survived despite centuries of suppression.

What binds these systems isn’t just how they were written, but why they were written. Across Africa, writing was a sacred, sovereign, and social act. It preserved not just knowledge, but identity. Hieroglyphics, however, remain the most globally recognized script from the continent, but they are often falsely disconnected from their African roots in modern Egyptology.

Africa Remembers Differently

What binds these systems isn’t just how they were written, but why they were written. Across Africa, writing was a sacred, sovereign, and social act. It preserved not just knowledge, but identity.

Whether carved into stone, woven into beads, or whispered through generations, these African systems of writing defy colonial silence. They reveal a continent that was documented, remembered, legislated, and imagined often in forms that are unrecognizable by others.

Africa didn’t lack writing. The world simply failed to read what we wrote. Now, it is up to us to re-introduce ourselves to the world and teach about the things that have been forgotten.